Your Identity and the Confusing Narratives About It

Over the weekend The Wall Street Journal published this opinion piece: “The Inauthenticity Behind Black Lives Matter” by Shelby Steele¹…

Subscribe to continue reading

Over the weekend The Wall Street Journal published this opinion piece: “The Inauthenticity Behind Black Lives Matter” by Shelby Steele¹…

Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to continue reading

Apparently, my gestation period is about ten years. I'm still thinking about the IA Summit I attended in Baltimore in 2013. I've been mulling over a keynote presentation by Scott Jenson.[1] During the presentation, Jenson named Malcom McLean as his hero. However, I had just finished reading a book putting McLean in a different context.[2]

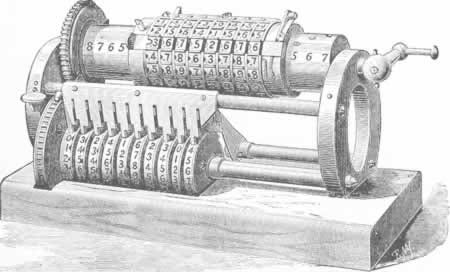

Malcom McLean made the world smaller. Modern globalization and its complexities are rooted in McLean’s seemingly simple invention, the shipping container.

By thoughtfully designing, standardizing, and then handing his patent to the International Organization for Standards (ISO) as a gift to the world, McLean stream-lined international trade and enabled consumers to wallow in more stuff than they ever dreamed possible.[3] Since their introduction, containers and their ships just keep getting bigger. Thanks to modern shipping, China is the virtual “workshop of the world.”[4]

Prior to flying to Baltimore, I finished Roberto Saviano’s dark expose of organized crime in Italy, Gomorrah. In the opening paragraphs, a crane operator disturbingly describes a shipping container opening and corpses spilling out onto the docks of a port in Naples. The dead are Chinese.[5]

I'm currently reading a crime and thriller series by Barry Eisler about a woman who is a cop hunting down the men who trafficked she and her sister. The first book was so brutal I had difficulty in many parts.[6] The book opens in a shipping container. Eisler's bare bones prose quickly takes the reader in and out of the shipping container using flashbacks and present-day interchanges.

For me, I can't separate shipping containers from human trafficking. It's not something I can forget or even ignore.

Before his death in 2001, McLean kept a low profile. He was personally and emotionally devastated at the bankruptcy of his company in 1986.[7] It’s unclear if McLean really knew shipping containers could be used in such nefarious ways. McLean was a builder from the same era as my grandfather, a construction prodigy, utterly self-made.

From McLean's perspective, containers solved a problem: the shipping of stuff. What the stuff is, how it’s made, who makes it, and from where its components come are logistics unseen by consumers. As Saviano writes, “All merchandise has obscure origins: such is the law of capitalism.”[8]

I am not painting McLean as a bad guy. Plainly, he was a businessman who changed the world. But contextual factors complicate his legacy. Just a few of them are:

Nearly a quarter into the 21^st century, shipping containers are just life around the world. Yes, they enable slavery, but people also retrofit them into cheap housing. It's a complicated, messy history, but one where context is critical.

[Scott Jenson. “2013 IA Summit.” Baltimore, MD, April 5, 2013.] https://www.slideshare.net/scottjenson/2013-ia-summit. ↩︎

I don't know Scott, and this isn't a critique of his presentation. It's memorable because his presentation didn't present the unintended consequences of design, something missing in most conference talks I've seen (unless the talk itself is about unintended consequences. ↩︎

Levinson, Marc. The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2008, chap. 14. ↩︎

Martin, Will, and Vlad Manole. “China’s Emergence as the Workshop of the World.” Policy Reform and Chinese Markets: Progress and Challenges, 2008, 206. ↩︎

Saviano, Roberto, and Virginia Jewiss. Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System. New York: Picador, 2008, chap. 1. ↩︎

Eisler, Barry. Livia Lone. First edition. Seattle: Thomas & Mercer, 2016. ↩︎

Levinson, 2008, chap. 12. ↩︎

Savioano, 2008, chap. 2. ↩︎

Díez, Federico J. “The Asymmetric Effects of Tariffs on Intra-Firm Trade and Offshoring Decisions.” Research Review, no. 13 (March 2010): 18–21. ↩︎

Mueller, Benjamin. “Gasping for Air: 39 Vietnamese Died in a U.K. Truck. 18,000 More Endure This Perilous Trip.” The New York Times, November 1, 2019, sec. World. [https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/01/world/europe/vietnamese-migrants-europe.html] ↩︎

I've been deeply studying context since 2012. I have an unfinished book on the subject because of where the research led. I'm ready to complete the book and this is now going to be my primary blog. I'll republish older content from previous blogs here with updates.

I've chosen the Ghost platform so I can have a newsletter and a potentially have some income from writing here. In the meantime, I'll be publishing articles as fast as I can write them. You're welcome.

Context is complex and everyone needs to understand it.

Subscribe to continue reading

They are reflective of the UX and development world's ivory tower, isolated, self-congratulatory culture. Many decisions are made in a…

Subscribe to continue reading

I’ve been in IT for over 20 years and this was news to me until last year. I’m no Luddite either. Not everyone is technically savvy and…

Applicant tracking systems (ATS) are an outcome of our economy. We have record levels of underemployed. Layoffs are getting bigger and are simply routine (I’m almost done with an article about this very topic). HP alone could end up dumping more than 80,000 people back into the job market since 2012. ATS are AI systems to help recruiters handle thousands of applicants. The irony of ATS is they also put people out of work. Automation exists to remove the human element.

I’ve been in IT for over 20 years and this was news to me until last year. I’m no Luddite either. Not everyone is technically savvy and those of us who work around technology all of the time can easily forget not everybody invests a large amount of personal time into learning every aspect of every system they come in contact with. I would rather hire someone who spends time developing work-related practical skills rather than knowing ATS inside and out, especially if the job in question isn’t in HR.

So I’ll respectfully disagree on that point. Layoffs are devastating enough. From personal experience, I can tell you there’s no way to prepare for having custom, keyword loaded resumes. The stress of job hunting plus needing to support families plus trying to learn new skills all add up. Most rock star practitioners I know sacrifice something personal, usually family, to keep themselves marketable. Just knowing you’ll probably never even be seen by a human for most jobs now plays mind games. I spent weeks tweaking resumes, burning midnight oil preparing documents for what is essentially a job lottery.

In that light, I hope one day we will figure out how terrible this is for everyone. Universities should prepare people to think conceptually rather than rote learning how an algorithm, which they have no insight into, picks apart keywords in 2016 but will probably change with each release.

Back in July, Tim O'Reilly posted about his What’s the Future (WTF) Conference, which is this week. O’Reilly’s article paints a picture of…

Back in July, Tim O'Reilly posted about his What’s the Future (WTF) Conference, which is this week. O’Reilly’s article paints a picture of the world upended and transformed, hardly familiar. He then writes, “The algorithm is the new shift boss.”

That shivers me timbers. I’m truly not cynical, but those are heavy words and unintended consequences being what they are, we must consider the bad with the good. O’Reilly wants to start a dialog about technology and the future of work. The first comment below his post from middle school French teacher, Léa Dufourd, reads: “When the ticket to go to the conference costs $3500, you already have a good idea at least of who is invited to think and design the future of work… WTF?”

O’Reilly’s response is more or less a defense that he is curating content and inviting people as well as providing discounts; fair enough. He runs all sorts of different events and some are free. However, WTF is specific to the future of work. His other events are not. It’s happening in San Francisco, so after airfare, hotel, conference fees, and food, a trip like that could be $5500 or more. That’s about 10% of the average annual teacher salary.[1] For me, that money represents the total amount of work I currently have to put into my aging, but paid-off van.[2]

Most people who are deeply affected by the issues O’Reilly mentions will never hear of his conference. Those not in the network of people planning, speaking, or attending WTF are excluded. If we don’t mix an already problematic Silicon Valley culture[3] with, say, people struggling to pay bills or with chronic illnesses, there is no context for any of the thought, business, and political leaders. They’ll just ride roughshod through the workplace like Donald Trump in a china shop. The Algorithm is the new elitist buffoon.

As a UX conference planner, I see first hand how easy it is for practitioners to stay sealed up in their little tech bubbles. We generally discuss how we work, but how we affect people outside of the user paradigm is a topic starving for attention. We are in such a rush to create addictive user experiences, we hardly notice a large swath of humans do not have access to the same technologies, disposable income, and discourse communities we do.[4] The higher the conference price, the more exclusive the group of people. The Algorithm is a product of the ivory tower.

We are losing control over our own lives as technology erodes the perceived need for us. According to the Greeks, circa 1200 BC, the gods of Mount Olympus were prescribers of fate. Some helped, some hindered, and some impregnated, but humans had little if any self-determination. Like the Greek gods, the Algorithm tinkers in our lives and most of us don’t know when or how. It works in the background affecting nearly everyone in the world, but only about 13% of the global population are actual programmers.[5] Even among the 18.2 million developers, not everyone truly understands how software works at all levels. The best-of-the-best programmers are with the more affluent business leaders using the most resources; think of them as demi-gods. The Algorithm is a faceless god.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a human creation. Like any bad code that goes into production, it’s not immune from ignorance. Programmers don’t understand everything about everything and probably don’t have context for what they are creating outside of vague bullet points written by a yuppie in a coffee shop. How does any AI know what productivity is when we can’t define it at the human level (see more on this below)? Imagine Siri saying, “If you have time to lean, you have time to clean.” The Algorithm is the assistant manager nobody likes.

Most job seekers are unaware their résumés are automatically filtered through applicant tracking systems (ATS). ATS look for keywords in résumés that match open job descriptions using undisclosed algorithms.[6] Assuming seekers are aware of ATS, they must rework their résumés for every job or risk spitting into the wind. This is the conversion from HR to Dehumanized Resources; the applicant pool is sifted to eliminate those silly people who can’t meet unexpressed expectations. Nobody gets to meet in real life. The Algorithm is the petty bureaucrat.

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

Voter tracking databases designed to find voter fraud may have disenfranchised nearly 7 million voters simply because of name matches. Most states participating in the Crosscheck program will not reveal whether or not they purged matches.[7] The Algorithm is the autocrat.

There are so many laws on the books, you can argue that ignorance of the law is a constant state of existence.[8] We blindly agree to whatever terms of service or disclosure is presented to us because to read and fully understand all of the disclosures we agree to is literally impossible. The more we agree to, the more we give up our constitutional rights.[9] The Algorithm houses the infoglut within a cryptocracy.

The rise of computer information technology (IT), in general, has given us the Productivity Paradox, a socioeconomic problem instead of a cool cyberpunk premise. In a book review, Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Solow famously, off-handedly quipped, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”[10] Ever since, economists have been working the problem. With knowledge work more fractured and ad hoc than ever, how do you begin to measure productivity when workers are interrupted about 88 times a day?[11] When IT budgets are increased to buy into more technology when workers don’t have a handle on their own time, it’s as if the workplace has become a living M.C. Escher painting. The Algorithm is the ouroboros.

People are increasingly acting as if they have disorders, alarming behaviorists worldwide. They show signs of addiction withdrawal and anxiety when separated from mobile phones. Many use online interactions to avoid real life social situations. ADHD-like behavior resulting from living split-screen lives probably doesn’t help the previously mentioned productivity paradox.[12] Researchers at Bournemouth University in the UK want warning labels on mobile technology in the same manner as alcohol and tobacco products.[13] The algorithm is the pusher man.

Breathless anticipation of the future feels fun and exciting, but like nearly every human invention, there are consequences. I don’t think the new shift boss is completely competent. He’s helpful when the circumstances allow, but he’s also an asshole. Everyone needs to be in this discussion.

Originally published at www.futureproofingcontent.com on November 8, 2015.

Here in north Texas, marching bands are large and competitive with their own cultures. My daughter’s high school band has around 260 kids…

Here in north Texas, marching bands are large and competitive with their own cultures. My daughter’s high school band has around 260 kids. They are a competitive band and the competitions are extravaganzas of massive orchestration. The complexity of the shows is stunning. My little high school band had only a couple of dozen kids and they just wore green polyester and marched in straight lines with the odd occasional left turn.

My daughter’s band, however, can take up nearly an entire football field when standing still and they quickly form large patterns like their high school’s letters while marching sideways and backwards in intertwining lines. The complexity of a set’s mechanics are almost a distraction from the performance itself. These elaborate band shows are modeled through software, but the execution is managed by section leaders and band directors. While directing by instrument and other organizational break-downs help make it easier to coordinate, in the end, the band has to operate together.

I use the opening act before band performances to process my working day. (The warm-up is an avant garde experiment with time displacement where giants donned in ceremonial faux-armor group, struggle, and regroup while searching for a pointy leather balloon. The surreal part of the performance is there is a clock that slows down, teasing you with the Theory of Relativity.) As I decompress and have sensory input outside of a computer screen, I reflect on Agile, Scrum, and the nauseating smell of liquid arena cheese.

I’m less enamored with Agile and Scrum as of late. I just don’t think it’s a one-size-fits-all system. The transition from Waterfall to Agile has been a little ugly. The unforeseen consequences are rearing their heads as we spend copious blocks time fixing things we broke in haste to make dates.

For example, with Waterfall, we had accounting systems that tracked project numbers. It wasn’t perfect, but if you knew the project number, you could search any internal system and find documents, diagrams, code, etc. Now, project numbers are peripheral. Those same systems (e.g. our testing and bug tracking system) are free-for-alls. The taxonomy of projects is based on whatever the person entering the data thinks of. It could be project name, number, or cutesy Scrum names you only know if you’re on those teams.

Agile is like vaguely written legislation. It’s open to interpretation and abuse. Part of the problem lies in the Agile Manifesto, published in 2001. Each tenant of the manifesto is utopian and lacks specificity. Agile is one of the best, neutral (i.e. not religious or political) examples I can think of demonstrating how philosophical underpinnings affect the execution of an idea. Unless the organization has absolute cultural practices that supersede process ambiguity, then things will stop getting done with each new process, for example, documentation.

Organizations who don’t have a strong content strategy embedded in its culture will lose knowledge when processes don’t unconditionally require matters of record.

Traditional software development methods seem clunky. Gathering and writing requirements is perceived to be arduous. Agile software development is a convenient excuse to shortcut research and documentation. On the surface this seems like a good idea. Who reads the requirements anyway?

Basic software documents like requirements, use cases, user studies, etc. have quick expiration dates. There’s no question about it. But it’s not the documentation that’s important — it’s during the exercise of producing traditional documentation when the magic happens. When business analysts work with developers to determine technical constraints, for example, they are providing context for everyone. Yes, this takes time, but the consequences of not going through those exercises is a future full of reconstructing knowledge often, meetings with the only goal of clarity, arguments over semantics, and a disregard for complexity and nuance.

There’s fast and then there are aimless, spastic, endless releases. The more release cycles are sped up, the more things we drop to meet deadlines. The larger the scale of software, the more complex its environment. While mobile apps lend themselves well to Agile, large enterprise applications interconnected with other large enterprise applications have layers of complexity you can’t deal with in a six-week sprint. At what scale does ambiguity across dozens or hundreds of autonomous teams no longer function?

I often feel Agile in large enterprises is like a big marching band without a planned show. We are all out on the field and left to our own autonomous teams who are trying figure out where to go to form the letter “T.” There is a band director and drum major signaling to us but they keep looking at the visiting team’s band for queues so we can improvise competitive moves. Then every once in a while the school’s principal shows up and yells at us maneuvers the district’s administration wants added into the show. And, by the way, we need to stop using one-third of the field because they’ve decided to add folding chairs there. Apparently we aren’t maximizing the potential revenue of the stadium.

Back in my Air Force days, I marched in the honor guard. Four of us worked together to present the flags at ceremonies. We were flexible enough to fall in with larger parades or individually, we could march with members from other services (i.e. the Army, Navy, and Marines). I know how to march and I have a snappy salute to boot. But I would never hold up in my daughter’s band because I learned military rather than band marching, the scale is much greater, and the purposes of each are distinct (not to mention considerable time has passed since then, but let’s keep our eyes on the pointy balloon).

Orchestration of so many people is strategic, not tactical. The trick, I think, is to work the process most applicable to the scale of the project. Using different methods for different circumstances, planning scalable processes, setting absolute standards for matters of record, and paying attention to what is and isn’t working are all more in the spirit, rather than the letter of Agile.

Originally published at www.mkanderson.com.

Yeah, the irony of using social media to criticize social media isn’t lost on me. Kind of like how the show Mr. Robot is produced by NBC Universal. I do like me some Medium, though. It’s not as hit and run as most.

It’s been a long time since I’ve sat down to actually write a serious blog post. If you don’t already know by my shameless self-promotion…

It’s been a long time since I’ve sat down to actually write a serious blog post. If you don’t already know by my shameless self-promotion, I’m working on a book. As I’ve mentioned before and to many people, I don’t want my illness to be a defining thing. Yet, there are some things I’ve learned.

I nearly died, several times over. I was intubated for three weeks. It’s not like TV, where coma patients hop right out of bed and begin killing everyone who put them there, as well as zombies. So many zombies.

Instead, recovery has been arduous and filled with false hopes, unimaginable frustration, and drugs, lots of drugs. One thing I began to notice during my recovery was my mind not working with me. Intubation took its toll: it was three years and several surgeries later before I could feel physically normal. My cognitive functions were also impaired from being put under for so many surgeries and all those drugs I mentioned erlier. My mind needed rehab too.

That’s why I’ve not been on social media much since 2011. At first it was just hard because when I woke up after intubation, I couldn’t even hold my cell phone; it was as if it weighed a hundred pounds. Later on, I would discover I needed glasses. Being in a pain-and-nausea-drug-fog blurs the vision and dulls the wit. In the meantime, my brain flew on autopilot.

There was a point where I was afraid I would lose my focus for good. My work was suffering and I feared losing my family, house, and any reason to live simply because I couldn’t think.

About a year ago, I talked to a neurologist. I had just had another surgery in May and felt that physically I was on the mend but my mental acuity was at its worst. After my conversation with the neurologist, I went on brain rehab. I paused social media indefinitely and dug into research for my book. Real research, not just Googling. I dusted off my library card and accessed EBSCO. I read challenging books by Robert Stalnaker, Peter Ludlow, and John MacFarlane. I also dug back into favorites from my dusty bookshelf by Walter Ong, Michel Foucault, and Charles Goodwin.

This all felt like I weighed 500 pounds and exercising for the first time. There were days I cried from frustration because things I previously never thought too much about were now challenging. For example, spelling. Even today I see red squiggly lines under typos and can’t figure out why the spell checker is flagging words.

This entire process taught me to appreciate focus. Getting off social media and putting my phone away has opened up a whole new world to me. It’s a world where you can study the tops of everyone else’s heads. In this world, you can observe people mentally derailing when they hear a notification. Sometimes you can infer from their expressions that they know they are talking to you, but the phone… It’s all something creepily similar to the world MT Anderson wrote about in Feed. The only difference is we don’t have a physical implant of the Internet in our heads. Yet.

My book is coming along now that I’ve crossed the threshold of pain it took to overcome such a tremendous emotional, physical, and mental setback. I don’t recommend you try it. I do, however, recommend you begin honing your own focusing skills.

The physical and virtual worlds are always with us, singing a siren song of connection, distraction, and options. We rarely are completely present in one moment or for one another

Maggie Jackson

First and foremost, read Maggie Jackson’s Distracted. Maggie is ringing the alarm about the world’s attention deficit disorder. I wanted to interview Maggie for my book and she was amicable about it but declined because we couldn’t meet face-to-face. This is impressive to me. Since I’ve never met her in person, and I can only assume this is true, but I bet it is: she must give those she interviews her full attention. It’s apparent in her writing that she is paying attention to detail and is hyper-aware of the technological distractions most of us consider life’s background noise.

Next, I recommend you set time limits to your social media dives. Think less than an hour a day. Your family will thank you. You will also realize that you don’t have to be attached to “the conversation” 24/7. It will still be there when you get back. Also, with 2016 around the corner, what will appear in your social media feeds will be offensive, ignorant, and divisive. Why get frustrated with people soapboxing their politics online anyway? I have pre-election social media dread already.

Also, establish boundaries. This is tough because we’ve collectively attached the same level of urgency to our interruptions. Where I work, there are days where I do nothing but respond to instant messages (IMs) as an ad hoc to-do list. This is especially difficult because responsiveness to those IMs is expected, but focused work like writing and research suffer immensely. I have been blocking time off on my calendars so I can have uninterrupted working sessions. During those times, I make sure my phone is put away too. Remember interruptions can also come from ourselves.

Finally, talk to others about distractions. Recommend Maggie’s book and use that as a starting point to frame how you are trying to be more productive. Tell people just because you don’t respond immediately to text messages or IMs, it doesn’t mean you love them any less. It just means you are trying to be productive and make a difference at work, at home, or anywhere you need to actually do something.

Thank you for taking the time and attention to read this. See? You’re already on a good start.

Originally published at www.mkanderson.com.

It’s nearly impossible to provide a precise, technical definition for context. We understand it through its use rather than by…

It’s nearly impossible to provide a precise, technical definition for context. We understand it through its use rather than by identification.(1) Judge Potter Stewart famously said the same about porn.(2)

For the purpose of content strategy, I define context as the collection of influences affecting the creation and cognitive processing of content. This oversimplified definition doesn’t serve the concept justice, but it’s a serviceable start for practitioners. As an added bonus, you don’t have to wade through nausea-inducing philosophical hair splitting. Everybody wins.(3)

Context is woefully under-appreciated in professional communication. When discussed, it is usually framed around the consumer of content. However, like language itself, context is interactive. You have contexts to consider, requiring potentially more attention than your audiences’. When you create content for your users, you are doing more than just writing copy or going through the motions of information architecture (IA) exercises. Context is a culmination of influences, making impressions as unique as fingerprints and complex as DNA. Those of us who create content cannot strip ourselves completely free from influences. You are representing your organization, but you’re also projecting culture, values, perspective, and a plethora of other factors into your work.

Have you ever been on a reading kick of something a little older and removed from every day language like Jane Austin, Charles Dickens, or even Dashiell Hammett and something you’re writing accidentally takes on their tone? Try binging on Steven King and not dropping the f-bomb while hammering out some document you could write in your sleep. Many novelists claim they have to sequester themselves while working on a first draft to prevent themselves from accidental shifts in tone, plot, and possible plagiarism. It’s a problem with the creative process in general.

Sam Smith’s song “Stay With Me” sounds an awful lot like Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.” Smith’s camp says they had never heard the song before.(4) While that makes me sad for the future, I believe them. I have teenagers and, in spite of my best efforts of cramming years of only the best rock into their skulls, they wouldn’t have made the connection either.

You can argue coincidence, Smith ripped off Petty, or they share the same simple musical fundamentals.(5) Smith might have heard “I Won’t Back Down” on an elevator or in a restaurant, maybe even years ago when his parents played it. The root cause is inconsequential to the listeners. Once they make that connection, they can’t un-hear it.

Now that Smith must write out a hefty check to Petty and Jeff Lynne, he is probably going to be hyper aware of sound-alikes as well as the cramp in his hand from so many zeros. He’ll probably never let this happen again simply because of this experience–his newly acquired creative context.

The only way listeners will make their connection between the two songs is familiarity with both, news articles, social media, noticing Petty and Lynne as credited writers, or anything that makes them aware of the connection–their potential, but not eventual, context.

All of this is to illustrate in a simple way that context has a life of its own. To implement a content strategy without considering both the creation and consumption sides of context will cause problems. You have to rely on the information you can collect about your audiences as well as becoming aware of your own influences. Just the exercise of documenting contexts in your content plan will go a long way to using context as a strategy.

This is a first in a series of articles about context as strategy. There’s more to come because I won’t back down.

Originally published at www.futureproofingcontent.com on August 30, 2015.